15. It Follows

Why is it that when an indie horror film gets critically acclaimed it immediately becomes hyped, but when a gazillionth haunted house / ghost movie hits theaters, including marketing campaigns on television, numerous websites and public space, we don't use the word "hype"? It Follows, like The Babadook, is a so-called hyped film, but what about Paranormal Activity, The Cabin in the Woods, The Woman in Black, Devil, The Conjuring, Insidious, Mama, Sinister, The Purge, Oculus, Annabelle or Dark Skies? Why aren't they accused of being hyped? It all feels like double standards to me, so I refuse to acknowledge It Follows is more hyped than any of the above. It's undoubtedly a popular film, a lot more than most other indie horror flicks. But so what? If you don't like it, you just don't like it, don't start whining about the film being overhyped. It Follows benefits from the 80s revival, just like The Guest, Ping Pong Summer, The Editor, The Final Girls and Turbo Kid, but it isn't an exploitation movie. While indeed the soundtrack is synth-based and the setting is really limited, its inventive ways to use a completely saturated genre (i.e. ghost stories) is effective and playful. Of course, this isn't a serious movie, nor will it bring about a shift in mainstream horror, but it is something authentically different from most commercial horror flicks these days - especially in its use of colors/lighting, score and casting. It might be that it isn't your cup of tea, even if you're a horror aficionado, just don't blame it for being overhyped (unless you only like obscure horror flicks, but why did you watch it then in the first place?). Finally, a thumbs up for (Brittany Murphy look-alike) Maika Monroe; I'm kinda curious what the future will bring for her!

14. What We Do in the Shadows

Probably one of the wittiest horror comedies in a long time. Vampires and werewolves have become boring and unscary. The 19th century has long gone by and that what makes us really terrified isn't to be found in books or movies anymore; let's just say global Newspeak is doing a better job on that front. What We Do in the Shadows knows scary isn't working anymore. Instead it rediscovers the banned-to-television genre of the mockumentary. Deadpan master Jemaine Clement (Flight of the Conchords) and Taika Waititi, forming the comic duo The Humourbeasts, came up with the idea in 2005 when they made the short What We Do in the Shadows: Interviews with Some Vampires. Vampirism wasn't as hip back then as it is now, but their patience has been rewarded: What We Do in the Shadows is probably one of the most popular films ever to hail from New Zealand (coming in after everything Peter Jackson-related of course). Some entertainment just is more creative than other, and it seems New Zealand has what it takes to make 'serious unserious' horror flicks: from Jackson classics Bad Taste and Braindead, to Black Sheep in 2006, to Housebound, What We Do in the Shadows and Deathgasm the last few years. Waititi has been signed to direct the third Thor installment (Thor: Ragnarok) in 2017. Let's hope something of his deadpan style makes it to the final cut of the new episode in the Marvel 'is-getting-old-real-fast' Universe...

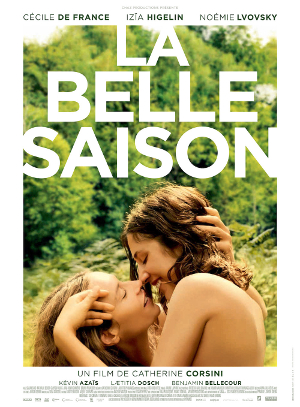

13. La belle saison

Isn't feminism supposed to be totally hip these days? Aren't many educated women self-proclaimed feminists? Or is most of it merely a fad, without real revolutionary vision and attitude, but a way of just identifying oneself? Being a man, it makes it difficult to proclaim that feminism nowadays is often a liberal pose (defined in terms of rights and career opportunities) than a true radical stance that concerns itself with anarchist, transgender or transnational issues. Luckily I see a lot of conflict within feminist organizations and movements, although politicians and other female authoritarian figures will often emphasize and embrace more white and privileged visions on feminism. Today, if feminism isn't just a trend to you, intersectionality is probably one of your main concerns. That's what La belle saison is all about. Unlike Suffragette, which is a representation of feminist history many like to see and applaud, La belle saison doesn't try to impose us with liberal superiority. This movie is really all about a romance between two women during the 1970s, not a way to divert feminist history away from people like Emma Goldman or Rosa Luxemburg and make it all about Emmeline Pankhurst and suffrage. Because of that, La belle saison is a very humane, complex film that doesn't push its viewers towards one side. It transcends liberal notions of femininity and oppression, and captivates its audience by way of its score, photography, humor, acting and dialogue. This movie is highly underrated and deserved so much more attention. Especially recommended for those who liked Olivier Assayas' Après mai.

11. The Big Short

The world is dictated by man-made laws being sold as natural, free-market laws. People in power get cynical because the whole situation feels inevitable: we are at the end of history and capitalism has triumphed, the only conflict left is of a cultural nature, not of an economical. That's the story we've been told since the end of the 1980s: communist, socialist, nationalist and statist ideologies are remnants of the past (as they should be) and we have nothing left to turn to. Free-market capitalism is possibly the biggest piece of smothering, dangerous and self-deceiving propaganda the world has ever seen. We get paralyzed by it. We get cynical. And because we get paralyzed and cynical, this propaganda becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The Big Short is a tale of this state the world is in, seen from the eyes of some of the naive hypocrites who sail the ship: hedge funders, rating agents, big bankers and businessmen, real estate agents, privately funded economic scientists, financial entrepreneurs, laissez faire capitalists, traders and stockbrokers, commercial journalists,... All those who safeguard the never-ending status quo of the financial and capitalist world. In The Big Short there are no good guys, not even the ethically confused Mark Baum (Steve Carell), the speculative Michael Burry (Christian Bale) or the disillusioned Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt). Sometimes they say or even do "the right thing", but in the end they all are trapped by the dictatorship of free-market laws they abide by, wish to preserve or see no alternative to. That's why The Big Short can be such a beautiful film: it embodies sheer free-market capitalism (A-list actors, big budget, sells criticism as a commodity,...), but it fails to glorify it through its content - it bursts the bubble of it being "free". Some might say it's cynical, but it's only cynical if you still hope for change while Wall Street or free-market capitalism thrive (or believe freedom and free-market capitalism can co-exist). The Big Short shows us that the system we all live in today is truly, inherently bankrupt (pun intended). And while our belief in free-market capitalism crumbles, the film proves that this "awakening" can be "taught" in a fun, gratifying way. It's like an enthusiastic, didactically dubious professor of economy has made an effort to explain the whole situation to us in a sexy and comic fashion. Or like a TED Talk where things get clarified as being beyond hope, as long as we expect solutions to come from reformist policies instead of revolutionary acts and the total negation of capitalism. Finally, The Big Short, for me, legitimizes the treatment of political and judicial authorities, financial institutions and those who propagate free-market capitalism with utter contempt.

Next up: films 10 to 6!

13. La belle saison

Isn't feminism supposed to be totally hip these days? Aren't many educated women self-proclaimed feminists? Or is most of it merely a fad, without real revolutionary vision and attitude, but a way of just identifying oneself? Being a man, it makes it difficult to proclaim that feminism nowadays is often a liberal pose (defined in terms of rights and career opportunities) than a true radical stance that concerns itself with anarchist, transgender or transnational issues. Luckily I see a lot of conflict within feminist organizations and movements, although politicians and other female authoritarian figures will often emphasize and embrace more white and privileged visions on feminism. Today, if feminism isn't just a trend to you, intersectionality is probably one of your main concerns. That's what La belle saison is all about. Unlike Suffragette, which is a representation of feminist history many like to see and applaud, La belle saison doesn't try to impose us with liberal superiority. This movie is really all about a romance between two women during the 1970s, not a way to divert feminist history away from people like Emma Goldman or Rosa Luxemburg and make it all about Emmeline Pankhurst and suffrage. Because of that, La belle saison is a very humane, complex film that doesn't push its viewers towards one side. It transcends liberal notions of femininity and oppression, and captivates its audience by way of its score, photography, humor, acting and dialogue. This movie is highly underrated and deserved so much more attention. Especially recommended for those who liked Olivier Assayas' Après mai.

12. Knight of Cups

Malick. Oh boy. If there's one director that polarizes audiences, it must be him. I couldn't bare some of the muddled reviews and pompous praise The New World, The Tree of Life and To the Wonder got. I saw his movies were special, unique and had a lot of creativity in them, but they all felt distant, unemotional and outright woolly. And that was exactly the problem. They all aspired to be spiritual, poetic and immersive; they were aimed at our senses and emotions, while they debunked more cerebral and rational approaches. Ironically, it was only in a rational way I could grasp this: I understood rationally what these movies aspired to be (which I applaud very much!), but I didn't feel it (so, in the end, to me, Malick failed). Enter Knight of Cups. The circumstances in which I saw this movie were almost exactly the same as I saw the previous movies, so it's not like I was high on drugs, was emotionally more invested or had a very receptive moment due to whatever cause. Nevertheless it overwhelmed me. Big time. It was as if Malick, after experimenting in his previous works, finally hit the right spot. The religious mumbo-jumbo of The Tree of Life was gone, as was the poetic celebration of love and romance of To the Wonder. Knight of Cups has - of course - a lot in common with Malick's older films, but its spirituality is more of an atheistic, contemporary kind (no Christian symbolism!), and its romance is more concerned with happiness / sadness and life / death than with downright emotions (no love story!). There's a reason why I thought the father-son relationship and the priest's speeches were some of the most redundant elements of the whole film: they reminded me too much of The Tree of Life and To the Wonder. Malick should let go of narrativity completely, because it distracts too much from the audiovisual and meditative flow of the moment. If Malick really is all about mesmerizing his audience, abolishing linearity while maintaining contemplative spoken word, should be his primary concern. In short: let go of meaning and let experience take over. Maybe Malick's magnum opus is still in the making.11. The Big Short

The world is dictated by man-made laws being sold as natural, free-market laws. People in power get cynical because the whole situation feels inevitable: we are at the end of history and capitalism has triumphed, the only conflict left is of a cultural nature, not of an economical. That's the story we've been told since the end of the 1980s: communist, socialist, nationalist and statist ideologies are remnants of the past (as they should be) and we have nothing left to turn to. Free-market capitalism is possibly the biggest piece of smothering, dangerous and self-deceiving propaganda the world has ever seen. We get paralyzed by it. We get cynical. And because we get paralyzed and cynical, this propaganda becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The Big Short is a tale of this state the world is in, seen from the eyes of some of the naive hypocrites who sail the ship: hedge funders, rating agents, big bankers and businessmen, real estate agents, privately funded economic scientists, financial entrepreneurs, laissez faire capitalists, traders and stockbrokers, commercial journalists,... All those who safeguard the never-ending status quo of the financial and capitalist world. In The Big Short there are no good guys, not even the ethically confused Mark Baum (Steve Carell), the speculative Michael Burry (Christian Bale) or the disillusioned Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt). Sometimes they say or even do "the right thing", but in the end they all are trapped by the dictatorship of free-market laws they abide by, wish to preserve or see no alternative to. That's why The Big Short can be such a beautiful film: it embodies sheer free-market capitalism (A-list actors, big budget, sells criticism as a commodity,...), but it fails to glorify it through its content - it bursts the bubble of it being "free". Some might say it's cynical, but it's only cynical if you still hope for change while Wall Street or free-market capitalism thrive (or believe freedom and free-market capitalism can co-exist). The Big Short shows us that the system we all live in today is truly, inherently bankrupt (pun intended). And while our belief in free-market capitalism crumbles, the film proves that this "awakening" can be "taught" in a fun, gratifying way. It's like an enthusiastic, didactically dubious professor of economy has made an effort to explain the whole situation to us in a sexy and comic fashion. Or like a TED Talk where things get clarified as being beyond hope, as long as we expect solutions to come from reformist policies instead of revolutionary acts and the total negation of capitalism. Finally, The Big Short, for me, legitimizes the treatment of political and judicial authorities, financial institutions and those who propagate free-market capitalism with utter contempt.

Next up: films 10 to 6!

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten